The key to the future is trust

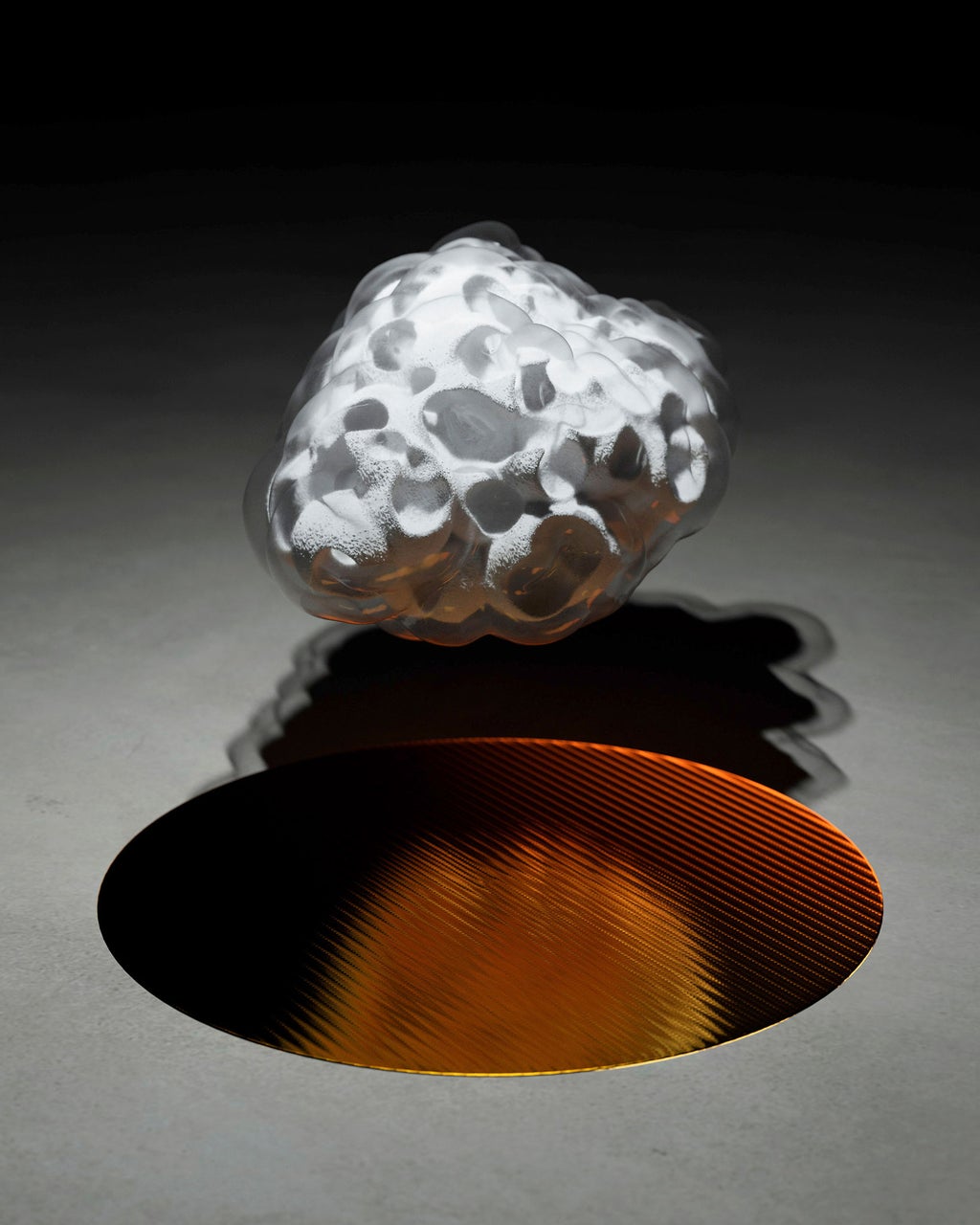

missing translation: fa.article-intro.reading-time – Interview: Bernd Zerelles – Artwork: Dean Giffin – Photo: Markus Rock – 05/02/2023

Professor de Haan, how would you define the future? Is the future a projection determined by past events, or is it a field of open possibilities?

It’s always both. Essentially, with everything we’ve done in the past and are doing now in the present, we’ve already arrived in the future, because that’s where the consequences of our actions take effect. On the other hand, things aren’t fixed in a way that means we can’t work with projections and come up with new ideas ourselves. Otherwise, we’d have to say there are forecasts that tell us what the future will be like, in which case we could lean back and think “I don’t need to take action, because the future will bring what it will bring anyway – it’s set.” But it isn’t.

Are futures researchers like yourself in particular demand during uncertain times like the present?

That’s been our experience, yes. There’s clear interest in answers that go beyond getting to grips with the pandemic in the short term. Compared with just few years ago, there’s far greater demand for us to present new or modified options for action within the context of the highly dynamic social change and high levels of innovation that exist today. We always try to take a participatory approach, often working with people on the ground, to generate ideas for the future and then situate these options within a larger context.

You analyze processes of social change. How does that work?

Futures studies isn’t primarily about forecasting in the narrow sense of calculating statistical probabilities. We operate with what you’d call probabilities in the everyday sense: probable developments rooted in plausible explanations. We try to identify good reasons for why certain developments might occur. We look at good reasons for why a certain development might continue or come to an end. But we also pay a lot of attention to the past, considering what the French so eloquently call longue durée. Are there developments that have already been going on for a long time? You can learn a lot from them too.

“Aestheticization is a universal trend. We invest things and events with a very personal significance.

Could you give us an example?

One example is the whole process of individualization that began two centuries ago, and in essence is far older even than that. Just think of our changing patterns of relationships. A hundred and forty years ago, people were bound to their marriages for life. Nowadays, we speak of serial monogamy. And there’s no longer a fixed gender binary either. Everything has changed, and it can all be very lucidly described in terms of processes of individualization. At the same time, there’s been a marked long-term shift towards a desire for greater participation, greater involvement in decision-making processes.

How are societies across the world changing at the moment? And what’s driving this change?

This desire for individualization is clearly observable all over the world, even in highly collectivist countries like China. Aestheticization the process of shaping our self-presentation is also a universal trend. Not just in the sense of presenting oneself as a member of a group by wearing a certain piece of clothing; rather, we invest things and events with a very personal significance. Objects, like cars of a certain brand for example, are no longer simply traditional status symbols. No, it’s more about needing an object because you yourself have infused it with meaning. It doesn’t matter what the product costs, but what value it has for me.

“Attitudes signal expectations of the future within a society.

Could you say that future is a mindset, an attitude?

Yes, definitely. The rediscovered concept of “attitude” combines a person’s norms, values, feelings, and other aspects of their mindset. Attitudes also signal expectations of the future within a society. For instance, younger groups are fashioning new lifestyles that embrace a digital world and regard it as central to their lives.

How can societies open up possibilities, create sustainable futures, produce innovations?

Just a few years ago, I would have said that you need a high level of individual freedom and liberalism, or that you need to cultivate individual creativity. Now I’m not so sure. You can no longer say those things are preconditions for innovation: the ability to design or develop something yourself. “Twenty-first century skills” like creativity and critical thinking are, fundamentally speaking, almost always imparted by initiatives based in new social groupings. So it’s collaborative systems and collective development, that contribute to innovations, rather than the actions of individuals. In other words, the creative intelligence of a heterogeneous team is greater than that of its individual members.

Do societies tend to change slowly?

Attitudes always develop slowly. You can see that clearly in shifts in lifestyles. Many of the lifestyle variants that have replaced traditional models of social class demonstrate that these sorts of changes don’t happen very fast.

Or are there factors that drive change more quickly?

There are also very strong drivers of change. For instance, disruptions resulting from highly dynamic new technologies that open up entirely new possibilities. I’m thinking of wearables, where people’s clothes communicate with each other. Or augmented senses, where information about other people is displayed to us when we meet them. There we can see something wholly new emerging. The question isn’t whether these innovations make sense or not when viewed from some higher vantage point. What matters is that they resonate with people. In an ideal scenario, potential users would say, “Fantastic! I didn’t even realize that was exactly what I needed.”

You once said that after a crises like a pandemic people return quickly to their old patterns of behavior.

Yes, indeed. Our habits are extremely stable, as anyone who attempts to make changes will have discovered. Every New Year, we say we’ll do more exercise this year. But how long do we keep it up? Or people who try to change their diet; most of them won’t stick with it. In both cases, we tend to fall back into our old ways of doing things, because those are very strong habits. There’s a strong desire to return to familiar patterns of behavior.

The fear of change processes is too great to break out of habits?

Those fears are greater in Germany than in many other countries. People here say that if we don’t know what consequences innovations will have, we should just leave things as they are. There are other cultures, like Brazil, the UK, or Vietnam, that think differently. The dominant attitude there is that if we don’t know what the consequences will be, well, we can at least try it out first.

So our perceptions of the future always depend on more than our own personal perspective?

Yes. People’s perspectives on the future vary greatly. One group that we might call “lovers of life” are very open to innovations. They judge the future in terms of what appeals to them. This group is very focused on leisure activities, they’re very dynamic, they’re always looking for new events and new things to surround themselves with. On the other hand, there’s a conservative milieu that doesn’t set much store by change. But what’s now become more important than these broad categories are small collaborative systems with just 50 or 150 people that form on social media. Not everything is decided collectively within these groups, because they too have their opinion leaders who say that so-and-so is important in this context and so-and-so in that one. But the crucial thing is that in these groups people feel like they’re not going down a certain path all by themselves, but rather as part of a community.

So people’s peer groups are crucial to change?

Yes, they play a very significant role. One very, very important issue in futures studies is trust. Which sources of information do we trust? Some people’s horizons are set by their trusted local paper. When it comes to issues relating to the future, the question is always: How do people develop trust in what you’re saying? I’m a member of the German National Academy of Science and Engineering. As a social scientist, other academy members often ask me how we can build acceptance for new technologies. I always reply: Before you can build acceptance, you need to ensure the technologies resonate with people. And that resonance needs to be based in trust in the innovations you’ve developed.

“The future essentially consists of projections.

Would you say that the acceptance of the future is based on trust?

That’s how I see it, yes. Because what’s your point of reference for the future? It’s not a reality we can observe. And in a dynamic society, we can’t address our expectations of the future by looking to past experiences. The future essentially consists of projections. And if you’re presenting these projections to people, you need to win their trust. Otherwise, they won’t believe the projections and they won’t become reality. The same applies to companies. They need to win trust in the ideas they develop. That’s a critical point.